Dana Voigt had just traveled to Italy and hiked up thousands of stairs. She had felt amazing and had no symptoms of illness.

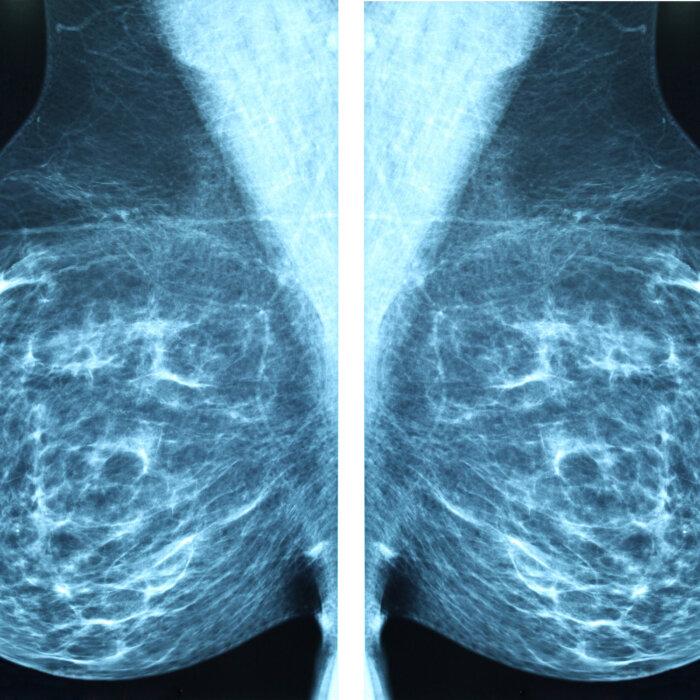

But after returning home, a routine mammogram revealed she had invasive lobular carcinoma—a hard-to-detect cancer that starts in milk-producing glands that turned her life into a whirlwind of information, appointments, and decisions.

Worst of all, while she wanted time to understand and absorb each bit of news, Ms. Voigt felt like her cancer team put her in a game of “beat the clock” that left no time to get a second opinion.

“I can’t think of anyone I’ve met who wasn’t overwhelmed and thrown into a tizzy on how to make a decision on something you have little to no experience with and you don’t even know what to ask or who to believe. You pretty much base everything on what the doctor and cancer team is telling you,” she said. “I was lost. I didn’t know which way to go, or how to think. I was in panic mode.”

There was something different about her breast cancer anxiety; Ms. Voigt described it as something she just couldn’t contain despite how hard she tried. Runaway emotions are common with a cancer diagnosis and treatment decisions—a major factor that undermines patient outcomes.

The Microbe Dimension

Anxiety is particularly troublesome for newly diagnosed cancer patients because stress has been shown to damage the gut microbiome, which is intimately connected to the immune system and predicts the success of some cancer therapies—both tied to prognosis.

New research has recognized this dilemma in a study that examined the intersection of the gut microbiome—the community of trillions of mostly bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in the gastrointestinal tract—and stress in the newly diagnosed breast cancer patient. The verdict: Patients who reported feeling distressed had marked differences in their microbial community that have been linked with various cancers, inflammatory bowel disease, poor treatment responses, and other negative traits that can affect quality of life even beyond treatment.

In other words, stress arising from a cancer diagnosis can also directly contribute to cancer itself. This raises the question of what doctors and cancer clinics can do to reduce stress and thereby improve cancer outcomes.

Patients, then, can also use new understandings of stress and its connection to the microbiome to enhance their microbial community—and prognosis—through lifestyle changes.

Microbiome’s Role in Breast Cancer

The new study builds on breast cancer research linked to the gut microbiome. The microbial community drives many metabolic, neural, and endocrine processes. It also acts as a gatekeeper of sorts for the human immune system, mostly by keeping pathogenic bacterial populations in check.- Specific microbes and the diversity of the microbial community have been linked to chemotherapy response and prognosis in patients. For instance, some bugs indicate a poor response to chemotherapy, whereas others show a beneficial response. Microbiota can predict chemotherapy-associated toxicity.

- An imbalance of microbiota, called dysbiosis, may lead to the development of breast cancer.

- Manipulating commensal bacteria—including using prebiotics and probiotics—has proven cancer-fighting potential in some patients.

her immune system with raw foods, supplementation, and detoxification. Though she didn’t realize she was nurturing her microbiome at the time of her 2011 breast cancer diagnosis, it’s a concept she’s now become more familiar with.

“Your microbiome changes and that might have allowed breast cancer to develop,” she told The Epoch Times. “But if you get out of your chronic stress, your microbiome may change back, and it helps your immune system fight everything.”

A Tale of 2 Microbiomes

The new study took a detailed look at the microbiomes of 82 breast cancer patients and noted significant differences in bacterial families and genera that coincided with distress and quality of life.Specifically, those with high levels of distress had more abundant Alcaligenaceae and Sutterella bacteria. Alcaligenaceae is a bacterial family that is associated with irritable bowel disease (IBD), chronic kidney disease, and several types of cancers. These bacteria—which are pro-inflammatory and typically higher in patients with depression without anxiety—are believed to play a role in the development or progression of disease, according to the study.

The family of Streptococcaceae was also more significantly abundant in those with lower distress scores in the study. Many of the bacteria in this family are health protective, help balance neurotransmitters, and have the ability to produce serotonin.

Could Urgency Be Problematic?

The urgency of treatment is something that may be contributing to stress, she said, though newer “watchful waiting”—or active surveillance—approaches are becoming more acceptable in certain scenarios.“All these bad things come in your head when you first get the diagnosis. They rush you, want you to hurry up. Even though that cancer’s probably been growing for 10 years, they want you in that surgery in a month. Not all doctors are like that though, but that adds to the stress,” Ms. Holcomb said.

It’s not uncommon for breast cancer patients to report “clinically significant levels of distress,” including angst over treatment decisions that can even continue for years, according to the 2021 article in Patient Education and Counseling.

Confusion Leads to Anxiety

The Patient Education and Counseling article said those who described their relationship with practitioners as trusting and supportive had reduced psychological distress—and they were more satisfied with the decisions made. On the other hand, some patients felt communication was confusing, and they left appointments with unanswered questions.“Decisional distress is important because it is expected to play a role in quality of life and decision satisfaction for breast cancer patients. Negative affectivity surrounding decision-making may contribute to overall distress, and general distress may contribute to negative emotions about treatment decisions,” the article stated.

The Burden of Weighing Infinite Options

Most oncologists will discuss only medical treatments such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. Within each of these exists a range of additional choices to be made depending on the type of breast cancer, as well as the stage, size, location, and growth rate of the cancer. Approaches may also take into account the health status, age, menopausal status, and preferences of the patient.A dizzying amount of decisions can be compounded by balancing life decisions since many breast cancer patients are women who work outside the home, as well as being caregivers to other family members, Ms. Holcomb pointed out.

Also weighing on many patients’ minds is whether they may need a mastectomy—surgical removal of one or both breasts.

“They don’t really tell you about what it’s going to be like, and I consider it an amputation,” Ms. Voigt said. “Even though it’s a body part I don’t need and can function without it, it’s still a missing piece. Some of that is stuff I dwelt on a lot in the beginning.”

Patients who receive chemotherapy or take Tamoxifen have an elevated risk of stroke as a side effect. Even though she didn’t have those risk factors, Ms. Voigt had high blood pressure and anxiety and had a stroke a month after her mastectomy.

Metastasis and Stress

Ongoing stress is especially problematic for cancer patients, because metastasis—cancer spreading to additional sites—is a concern during treatment.

Taking Simple Steps

Even well-meaning information can become burdensome, as patients often take on the responsibility of researching diet, stress-reduction tools, new studies, and more.

“We tell them so much that we can overwhelm them ... and the last thing you want is stress,” Ms. Holcomb said. “I always tell people when they can’t figure it out, pray for discernment. We tell them to go at their own pace, and if it feels right, they will know. Hope is important. It takes the stress away.”

Incidentally, many treatment options available outside conventional models are behavioral changes that influence both stress and the microbiome.

Help Beyond the Hospital

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) said complementary options are helpful to manage the side effects (stress, nausea, and vomiting) of treatment, such as music therapy, mindfulness meditation, stress management, yoga, acupressure, and acupuncture.

However, the organization warns that “most natural products are unregulated, so the risk of them interacting with your treatment and causing harm is uncertain.”

- Get distracted—Learn a new hobby or take up an interest.

- Meditate/visualize/relax—These practices can relax the mind and body.

- Be organized—Break down tasks, seek help, and use tools to keep track of treatment and everyday life.

- Get counseling—Either with a professional or a confidant, talk to someone you can trust about your feelings.

- Be physically active—Regular exercise can be good for the body and the mind.

- Take up yoga/tai chi/qigong—Ancient practices can reduce stress.

- Get outside—Sunlight, fresh air, and the sounds of nature are all soothing.

- Eat well—Choose real food for nourishment.

- Get adequate sleep—Sleep is vital for immunity. Shoot for seven hours per day.

- Join a support group—Talking to others who understand is helpful, and groups can offer information and education beyond what you find in a doctor’s office.

- Do something relaxing—If you enjoy gardening, listening to music, reading, or sitting with your pet, make the time to do these things you enjoy.

- Laugh—Consider reading a funny book or watching a comedy.

- Write in a journal—The act of writing out feelings is therapeutic.

Consider Detoxing

Another important consideration that can affect the microbiome, Ms. Holcomb said, is to cut back on exposure to toxins such as pesticides and flame retardants, antibacterial products, artificial sweeteners, and sources of chronic stress. A cancer diagnosis can be a good opportunity to address emotional well-being.“I know people will do everything to heal. They will do surgeries. They will do diets, clean up everything, and detox, and they’re still not getting better and the cancer is not moving. But then as soon as they forgive or deal with something chronic from their past, they begin to heal,” she said.

Two popular methods for this kind of emotional work are cognitive behavioral therapy and journaling.

“You can remove stressors. There are so many ways. It depends on you,” Ms. Holcomb said.