Sometimes, microbiome terminology is like the science itself: unfamiliar, incomplete, and confusing. Dysbiosis is no exception.

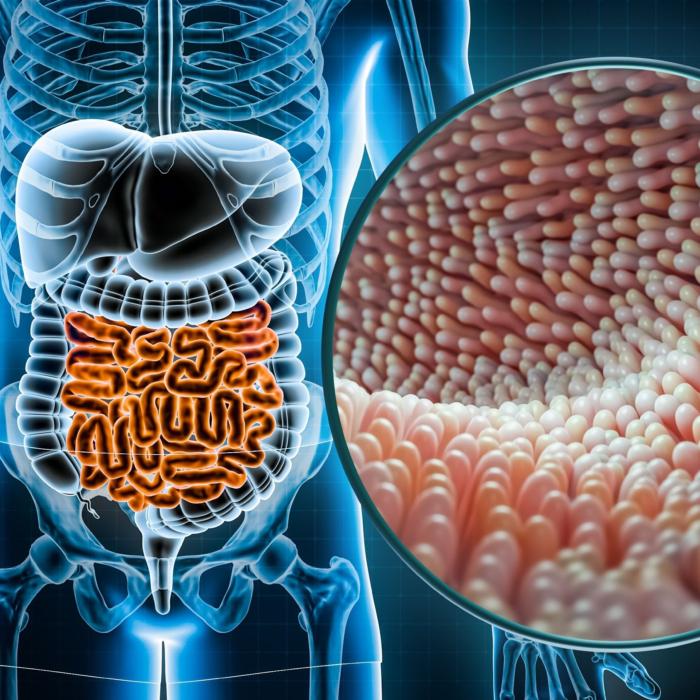

Dysbiosis is often used as a synonym for “imbalanced” when describing the state of someone’s microbiome. The problem is knowing what constitutes balance when there are trillions of bacteria—not to mention viruses and fungi—in the human gut.

It’s this diversity that makes it hard to determine whether we have all the right bugs in the right amounts.

Despite being poorly understood, studies continue to link gut microbiota to diseases of the gastrointestinal tract—and beyond. Dysbiosis is a biomarker of several disorders and a priority for future therapies to prevent and treat diseases.

A Balance of Bugs and Disease

Research is just scratching the surface of what dysbiosis is all about. A research review published in Microorganisms in 2019 looked at 113 studies to examine the state of science around gut microbiota balances.“Dysbiosis of gut microbiota is associated not only with intestinal disorders but also with numerous extra-intestinal diseases such as metabolic and neurological disorders,” the review authors wrote.

Insight about how the composition of our microbiome affects disease should help open new therapeutic options for those diseases, the researchers wrote.

- Irritable bowel syndrome is associated with a loss of microbial richness, which could affect the integrity of cellular junctions and weaken the epithelial barrier.

- Studies of celiac disease demonstrate patients have a reduction in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and an increase in potentially pathogenic bacteria compared to healthy subjects.

- Obesity is associated with lower species diversity, as well as lower levels of genes involved in metabolism.

- Patients with dementia have lower microbial diversity and disturbed microbiota associated with inflammatory states.

- Studies show a less diverse gut microbiome in children with autism spectrum disorders, as well as lower levels of Bifidobacterium and Firmicutes.

- Stress has been shown to have a relationship with gut microbiota, with specific changes that are associated with depression and others with stress.

- The gut microbiota of colorectal cancer patients had more of some bacteria and fewer butyrate-producing bacteria.

- Several studies found the gut microbiome is altered in patients suffering from Type 2 diabetes.

Our Microbiome Fingerprint

Correlation doesn’t equal causation. Though researchers have linked certain microbiome types to certain diseases, we don’t know if the bacterial imbalance caused the disease or was caused by the disease. Or maybe some other factor contributes to both a disease and a shift in the microbiome. Further complicating the study of dysbiosis is the fascinating fact that microbiomes are unique to cultures and even individuals.Divided Philosophy

Mainstream medicine tends to lean toward a more conservative approach regarding dysbiosis, only acknowledging its role in a handful of scenarios such as pathogenic infections like Clostridioides difficile (c. diff). On the other hand, researchers are continuing to link different bacterial profiles to different diseases and many functional medicine doctors will use stool tests to discern if levels of certain beneficial bacteria are low and try to increase those for disease prevention.Though it can require a lot of detective work, Palanisamy said there are thousands of studies coming out every year and many affirm dysbiosis and its role in autoimmune diseases.

Individualized Treatments

Most cases of dysbiosis tend not to be “lightning strikes,” meaning they aren’t often a chance event, Dr. Scott Doughty, an integrative family practitioner with U.P. Holistic Medicine in Michigan, told The Epoch Times.Rather, he said, gut issues tend to be the result of lifestyle—stress, toxins, nutrient deficiencies, and genetic complications with an occasional lightning strike. The good news is it makes dysbiosis reversible.

He doesn’t have hard rules, such as removing all gluten and dairy that he said give him the uncomfortable feel of “conveyor belt medicine,” although he does make dietary suggestions on a case-by-case basis before introducing supplements.

On the other hand, the library is filled with books from doctors who do offer blanket recommendations for healing the gut. Clearly, there’s a market for that, and they have helped plenty of people lead a more healthy lifestyle.

Palanisamy uses the method he wrote about in his T.I.G.E.R. Protocol, with T.I.G.E.R. an acronym for toxins, infections, gut, eating, and rest.

It takes a minimum of three months to start experiencing results from the protocol, which is designed to take a committed, holistic approach to the gut, he told The Epoch Times.

Doughty said while the books and products can be useful, he often suggests patients push them to the side once they begin working with him.

The Glyphosate Conundrum

Besides antibiotics and stress, another factor affecting microbial balance could be toxins that make contact with the colon through food. Studies indicate that an array of toxins can alter microbial composition, including one chemical that everyone has broad exposure to: the herbicide glyphosate.The CDC offers no toxicity, health, or regulatory guidance and states the assessment of exposure “does not by itself mean that the chemical causes disease or an adverse health effect.”

- comprising our ability to detoxify toxins.

- impairing the function of vitamin D.

- chelating iron, cobalt, molybdenum, and copper out of the body.

- impairing our synthesis of tryptophan and tyrosine, amino acids vital to protein and neurotransmitter production.

Perlmutter writes that the relationship between glyphosate and celiac disease is undeniable though other variables are probably at play.

“One thing we do know from recent research is that glyphosate does in fact impact gut bacteria,” he wrote.

Dysbiosis but Not Illness

It’s a frustration in science that even when a bulk of evidence looks suggestive, causation is difficult to prove, which is why vocabulary is important. As Grinspan said, one danger of using the word dysbiosis in place of imbalance is that it’s uncertain whether it’s always indicative of illness. People in urban areas have a less diverse microbiome than those who live rurally, for example.“This really gets a little complicated. People will jump on the term ‘dysbiosis,’” Grinspan said. “The microbiome is different in every single person. There’s so many different things that can affect that.”

It’s the sort of dilemma that functional physicians like to tease out—even if the science is still in its infancy.

As research evolves, Palanisamy said microbiota “signatures” of bacterial dysbiosis are emerging—patterns that reflect specific disease states. Some of them he mentions in his book are linked to multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and ankylosing spondylitis.

“There are a lot of different types of dysbiosis,” he said. “We haven’t understood them all fully.”