Donna Schwenk’s kitchen is overflowing with bacteria. That comes as no surprise after more than two decades of culturing food for healing—first as a personal mission to heal her baby, and now for her business.

Still, she was a bit reluctant to try out a new bacteria. Afterall, her health was in tip-top shape, and her business, Cultured Food Life, was growing. The author of three bestselling books and a podcast host, Ms. Schwenk had her hands full with her courses teaching others the ins and outs of how to make their own fermentation labs at home.

She reluctantly began culturing yogurt with a new bacterial strain—Limosilactobacillus (formerly Lactobacillus) reuteri—at the encouragement of Dr. William Davis, a cardiologist and author of several books including “Super Gut.” Dr. Davis also asked her to eat it daily for a year.

“It blew my mind. I thought I was really smart. I thought I knew everything,” Ms. Schwenk said. “They use L. reuteri to clean fermentation vats because it’s so strong.”

She said the human gut is also a fermentation vat of sorts because it nurtures the growth of many different bacteria, some of which may also need to be cleaned out. That’s where L. reuteri comes in.

“It will kill all the other [microbes] that don’t belong there, and it will thrive. That’s why it’s working so well for people, because in that upper gastro area, without L. reuteri, you start having problems if you get other bacteria in there,” Ms. Schwenk said.

She began to offer it to friends, including one who had chronic diarrhea and couldn’t leave the house. Relief from pain and embarrassment came in just a few days. Other testimonies included improved energy and mental health, less muscle fatigue, easier breathing, appetite suppression, and more.

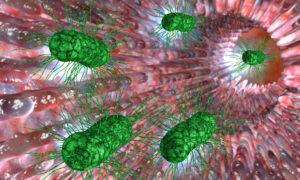

A single bacterial species can have widespread effects in the gut by altering the entire community of microbes in the human microbiome—the total collection of bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

L. Reuteri’s Origins

Discovered in 1962, L. reuteri colonizes human gastrointestinal tracts and can withstand a wide range of pH environments, making it a rare beneficial bacteria that can proliferate in the small intestine. Typically, bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine can lead to digestive problems, but that isn’t the case with L. reuteri. Back when it was discovered, L. reuteri was found in about 30 percent to 40 percent of the population. A Science Daily article in 2010 said its presence had shrunk to 10 percent to 20 percent by then. Dr. Davis and others claim its level is now at 4 percent.“Even though reuteri is ubiquitous in mammals and in indigenous human population like New Guinea or in the Brazilian rainforest, almost nobody in the modern world has reuteri anymore because we’ve all killed it,” he said.

About half of the mothers from Japan and Sweden had L. reuteri in their milk. Mothers in South Africa, Israel, and Denmark had very low or undetectable levels. Urban and rural living didn’t appear to play a significant role, although the authors speculated that diet could be a factor. The Japanese diet, for instance, is high in functional, probiotic, and fermented foods.

L. Reuteri and Gut Infections

L. reuteri appears to have a bi-directional relationship between gut health and disease. Several studies have shown that L. reuteri’s antimicrobial properties are nature’s version of an antibiotic—capable of protecting the body from gut infections.H. pylori infections are a major cause of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcers, in addition to a risk factor for gastrointestinal (GI) cancers. L. reuteri supplementation is particularly effective at decreasing the bacterial load of H. pylori when both are competing for food and resources. Some studies have shown that L. reuteri has the potential to completely eradicate H. pylori.

The Rise of SIBO

It’s a logical theory that L. reuteri’s disappearance is linked to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which makes its reintroduction to the GI tract a compelling alternative to harsh prescription antibiotics for the condition.“The SIBO gets pushed back by this microbe. There’s a variety of ways to gauge that, including if you test,” Dr. Davis said.

Diseases Associated With L. Reuteri

Weak intestinal barriers—sometimes called “leaky gut”—have been implicated in a number of diseases, particularly autoimmune diseases. According to the 2018 Frontiers Microbiology review, many studies have shown that L. reuteri induces anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells, or Treg cells, which play a role in preventing autoimmunity, suppressing cytokine storms, and limiting chronic inflammatory diseases.This makes L. reuteri a good candidate for disease prevention, as well as symptom management. “Indeed, the therapeutic potential of various L. reuteri strains has been studied in diverse diseases and the results are promising in many cases,” the study authors wrote. “The safety and tolerance of L. reuteri has been proven by the numerous clinical studies.”

- Colon Cancer: Low levels of L. reuteri and reuterin levels are linked with colon cancer, according to research published in Cell in 2022. The study found that L. reuteri was protective against tumor formation in the colon, with reduced L. reuteri and reuterin levels found in mice and humans with colon cancer. In mice, both the bacteria and its metabolite were found to decrease tumor growth and prolong survival.

- Obesity and depression: One L. reuteri strain was shown in a 2023 Frontiers in Pharmacology study to alleviate depressive-like behaviors and obesity co-morbidities in mice. They experienced improved blood lipids and insulin resistance. The bacteria also reduced liver inflammation, tightened intestinal junctions, and alleviated dysbiosis, or the overall imbalance of gut microbes.

- Constipation: Use of L. reuteri for symptoms of gas, abdominal pain, bloating, and incomplete defecation led to better outcomes over a placebo in a double-blind trial published in 2017 in Beneficial Microbes.

Proceed With Caution

While this microbe is very promising, there are some caveats. First, there are many different strains of L. reuteri that appear to have specific applications.“[M]ixed strains might get out of control due to the inconsistent reproduction speed of each strain, thus disturbing the balance and hindering the control of microecology,” the review article stated.

Weak strains were a concern for Dr. Davis, which is why he cultured the bacteria in yogurt using a supplement dose intended for newborns, which was the only one available when he began his investigations. Using flow cytometry, he was able to ferment and multiply the dose from 100 million to 300 billion.

“So far, every observation made in mice is proving true in humans, seen anecdotally and in clinical trials,” Dr. Davis said. “In other words, a lot of the modern phenomenon we’re seeing recede by recolonizing the upper intestine with reuteri.”