Is the Gut Really a Second Brain?

An article published in Science in 2019 introduced evidence that gut microbes determine whether the central nervous system and the social behavior of animals can develop normally. One study found that mice raised under sterile conditions without microbes in their guts had abnormal brains and social impairments. When researchers implanted microbes in the guts of the mice, their brain function recovered, and they started socializing with their own species. However, they couldn’t recognize familiar mice because the lack of gut bacteria at a younger age meant that they missed opportunities for brain development.You may have heard the gastrointestinal tract referred to as the “second brain.” The digestive system and the brain do have many similarities but also many differences. The brain has cognitive functions, learning and memory, advanced neural activities, and emotional regulatory functions, which aren’t available in the digestive tract, so it isn’t exactly true to say that the gut is a “second brain.”

The Two Nervous Systems

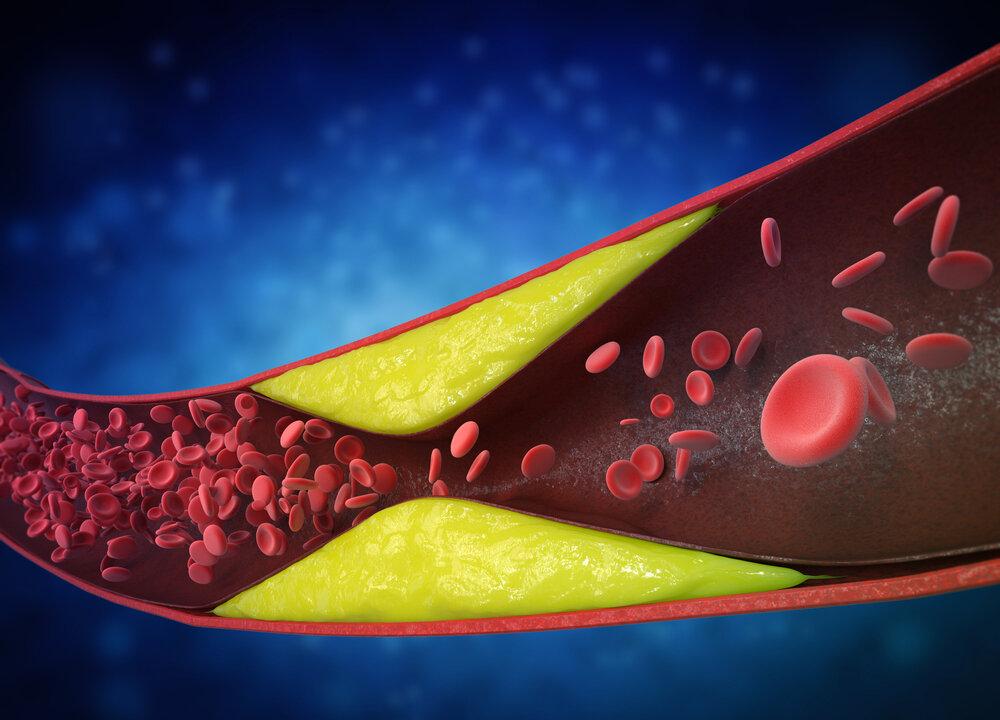

There are two nervous systems in the digestive tract: the local gastrointestinal nervous system and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves known as the vagus nerve. The parasympathetic nerves are connected to the brain and control digestion and absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, secretion of gastric juice, intestinal hormone secretion, immune function, and more. The brain can affect the function of the digestive tract by regulating the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and the digestive tract can also affect our thinking, mood, and behavior by sending signals to the brain.How do the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems affect the function of the digestive tract? The sympathetic nerve is the nervous system that’s excited when we’re in a state of fight or flight during an emergency. It will make our digestive tract reduce blood supply, stop secreting digestive juice, and weaken peristalsis so as to transfer more blood and energy to other parts of the body to deal with danger. The parasympathetic nerve is the nervous system that’s excited when we’re in a state of relaxation. It will increase the blood supply to our digestive tract, secrete abundant digestive juices, and strengthen peristalsis to activate digestion and absorb nutrients from food.

Rest and Digest

The ancient Chinese used to say, “Don’t talk while you eat; don’t talk while you sleep.” This motto comes from “The Analects of Confucius,” which tells us something about the behavior of Confucius himself—that he was very attentive while eating and sleeping and refrained from talking during meals. On the contrary, modern people often chat, scan their mobile phones, or watch TV while eating. Even worse, some people eat in a rush or while stressed or watch nerve-wracking or scary things while eating, which excites the sympathetic nerves, preventing the secretion of digestive juices, stopping peristalsis, reducing the blood supply of the digestive tract, and causing various gastrointestinal problems.Doing just one thing right can significantly improve our gastrointestinal function and help prevent stomach diseases: Relax during mealtime and focus on mindful eating.