Increases in human life expectancy, which nearly doubled over the past century, may be slowing, according to a new study.

While advances in medicine, diet, and public health have helped people live longer, the researchers found that a time when most people will live beyond 100 may be further off than many experts had hoped.

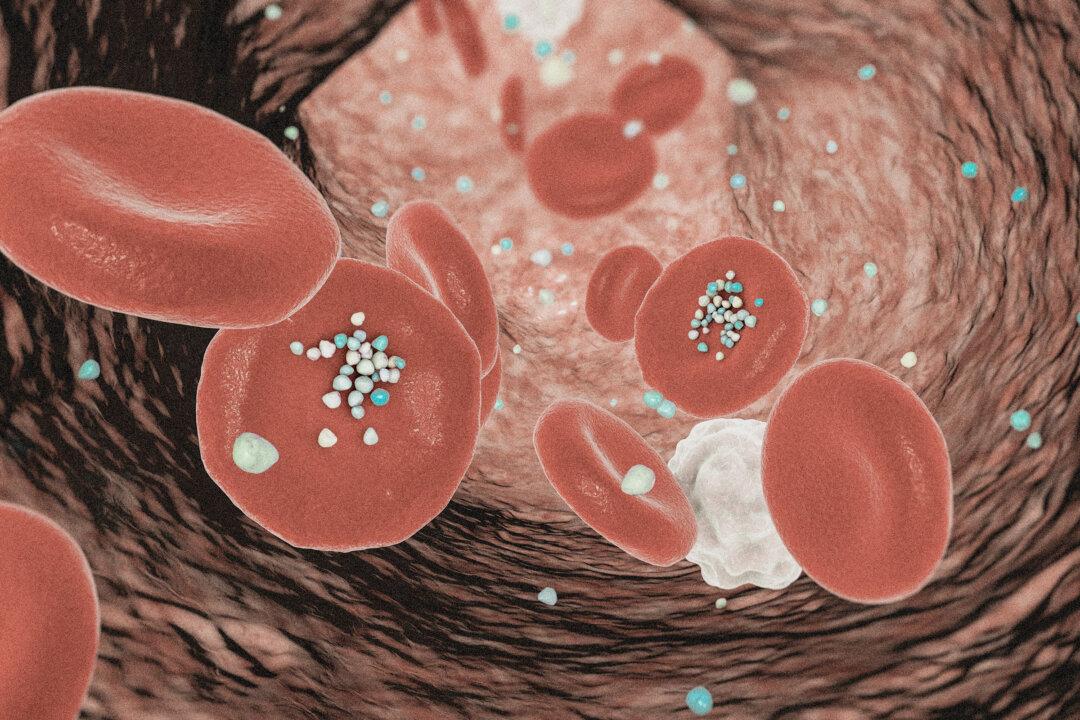

This is because while people are no longer dying from infectious diseases, they are now succumbing to age-related diseases that occur from biological aging.

“Unless the processes of biological aging can be markedly slowed, radical human life extension is implausible in this century,” the authors wrote in their study.

Dr. Nir Barzilai, a world-renowned leader in geroscience (the study of biological aging and age-related diseases), pushed back against the study’s conclusion, noting that while the statistical ceiling for human lifespan may be around 100, the biological ceiling is 115 years.

Slowing of Life Expectancy Gains

The study, which analyzed mortality data from the 1990s to 2019 across nine wealthy countries, including Australia, South Korea, and the United States, found that life expectancy increased by just 6.5 years on average during this period.Although life expectancy continues to rise, the pace of improvement has slowed. In 1990, the average rate of improvement in high-income countries was about 2.5 years per decade. In the 2010s, it was 1.5 years.

This represents a significant deceleration compared to earlier periods.

Women continue to outlive men.

Life expectancy is the average number of years a newborn is expected to live, assuming current death rates remain unchanged. While this measure is crucial, it is imperfect—it doesn’t account for unpredictable events such as pandemics or medical breakthroughs that could alter survival rates.

In the United States, life expectancy reached 78.8 years in 2019, but the rate of increase slowed significantly between 2010 and 2019. This analysis excluded the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a sharp decline in U.S. life expectancy.

Based on these trends, the study authors predicted that life expectancy at birth will not exceed 84 for men and 90 for women. They also estimated that only a minority of newborns today, or 15 percent of females and 5 percent of males, will live to 100.

Challenging the Idea of Radical Life Extension

One of the study’s major conclusions challenged the idea that most people born today will live to be 100 or older. Olshansky said that while some individuals may surpass 100, these cases will remain exceptions, not the norm.He added that their results challenge the commonly held belief that humans are on the verge of reaching a natural maximum lifespan. “Instead, it’s behind us,” he said.

This finding pushes back against industries, such as insurance and wealth management, that increasingly make calculations assuming that most people will live to 100. Olshansky said that this assumption is “profoundly bad advice,” as only a small percentage of the population will likely live that long in this century. “We’re talking about outliers, not the average,” he said.

The rapid acceleration in life expectancy growth observed during the 20th century was partly due to the control of infectious diseases and the rise of public health measures. But at this stage, gains have slowed. Moreover, there are new challenges, such as chronic diseases, a result of having an aging population.

“It’s the biology of aging that drives diseases,” Barzilai said. “You can be born with genes of Alzheimer’s, but when you’re born, you don’t have Alzheimer’s. When you’re 1 year or 10 years or 50 years old, you don’t have Alzheimer’s. It’s the aging process.

“This aging process is what we’re trying to target so that we can prevent diseases. Now, if we prevent disease, it means also that we live longer.”

“We already have diets, exercises, medicines, whole body scans, cancer-detecting blood tests, and medical procedures that can extend life by many years when implemented,” he said in an email to The Epoch Times.

While Sinclair, who is a genetics professor at Harvard Medical School, said he agrees that we are still a long way away from living to 150 with current technology, he believes future generations may see significant advancements.

“Children born today will see the 22nd century, and who knows what technologies will be available then,” he said, comparing the current state of technology to the state of transportation in the 1800s, when the fastest humans could travel was by horse. “To say the fastest humans could ever travel is a gallop would be wrong.”

Pushing Through the ‘Glass Ceiling’

The idea of a “glass ceiling” on human lifespan is central to Barzilai’s view of the future. “We have a roof, and we could achieve something with the right medical interventions,” he said. “We can push through this glass ceiling by slowing the biological effects of aging.”Barzilai said he believes that in the future, by targeting aging itself, medical science may be able to significantly improve healthspan, allowing people to live longer and healthier lives, even if they don’t surpass the 115-year mark.

“It’s one thing to say we cannot extend lifespan, but the bigger question is whether we can make the years leading up to 115 healthier and more productive,” Barzilai said.

Olshansky said he advocates for a shift in focus from longevity to “healthspan”—the number of years a person remains healthy, not just alive. He said that extending life expectancy could be detrimental if those added years are not lived in good health.

He said we need greater investment in geroscience, which is focused on biological aging and age-related disease, and which may hold the key to the next wave of health and life extension.