Exercise and Blood Sugar Control

Diet is a significant factor in controlling blood glucose and insulin sensitivity, and growing evidence suggests that exercise may be even more critical.The study compared aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, and the combination of the two to determine how they affect insulin sensitivity, blood glucose levels, and overall cardiometabolic health. Researchers also evaluated how the intensity of exercise and the time of day when the activity is undertaken influence glucose control.

Best Types of Exercise

Mr. Malin and his team analyzed several studies to summarize types of exercise and the best time to do them to improve blood glucose levels and insulin sensitivity. “I think of exercise as a drug,” he said.Aerobic Activity

Aerobic exercises such as walking, jogging, biking, and swimming use large muscle groups and usually increase heart and respiratory rates. Aerobic activity lowers blood glucose levels and increases insulin sensitivity using two pathways.First, muscle cells use insulin in the bloodstream to take up glucose during exercise. The same cells can also take in glucose without the help of insulin. By using both pathways, muscle cells remain sensitive to insulin for up to 48 hours.

Muscle cells also store more glucose inside the muscle for future use, leaving less traveling around in the blood, which is ultimately the goal. According to study researchers, participating in bouts of exercise favors insulin sensitivity and contributes to better aerobic fitness, thereby reducing cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in Type 2 diabetics, regardless of body weight.

- 50 minutes three times per week.

- 30 minutes five times per week.

- 25 minutes six times per week.

The study also showed that exercise can improve overall glycemic control. For instance, overweight individuals with an exercise routine of 45 to 60 minutes per session four times per week, working at 50 to 75 percent maximum effort for six months, reduced fasting blood glucose by 18.58 milligrams/deciliter and reduced insulin levels by 2.91 milliunits/liter compared with the group that didn’t exercise.

Researchers reviewed an epidemiological study that reported a 21 percent reduction in diabetes-related death after a 1 percent reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c or A1c).

Resistance Training

Resistance training can augment aerobic exercise by providing variety and increasing adherence to an overall training regimen. It can also help combat low muscular strength and muscle mass decline, independent risk factors in Type 2 diabetes.According to the ACSM, resistance training in older adults with Type 2 diabetes resulted in a 10 to 15 percent improvement in strength, lean mass, blood pressure, blood lipid levels, bone mineral density, and insulin sensitivity. Resistance training also led to more significant reductions in A1c.

Best Time to Exercise

Choosing the time of day and whether to exercise before or after a meal can significantly affect long-lasting blood glucose control and prevent spikes throughout the day.Circadian rhythm has a substantial influence on glucose control. There are several physiological processes, such as glucose tolerance, circulating insulin, body temperature, and hormones, that scientists have started to associate with glycemic control.

According to the AJM Open study, most research has found that exercise in the afternoon or evening may be better for glucose control and insulin sensitivity than the same activity done in the morning, though not all studies yielded the same results. Some research suggests that morning exercise is better for managing weight and keeping to an exercise routine, which could mean the best time to exercise may be outcome dependent.

Take Breaks From Sitting

Adults in the United States spend an average of eight hours per day being sedentary, which has become an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes.To offset the adverse effects of sitting, the AJM Open study suggests getting up and walking every 30 minutes, which can improve glucose and insulin sensitivity in people with Type 2 diabetes.

The soleus muscle runs from the back of the knee down the back of the shin bone to the heel. It’s used when walking and running and helps keep us from falling forward while standing. It’s built for endurance and doesn’t rely heavily on intramuscular glycogen, so it gets most of its fuel from glucose in the bloodstream.

The soleus pushup is done while sitting. According to the study, moving the muscle up and down yielded a 52 percent improvement in blood glucose and 60 percent less insulin requirement over three hours after a glucose drink.

Blood Glucose and Insulin

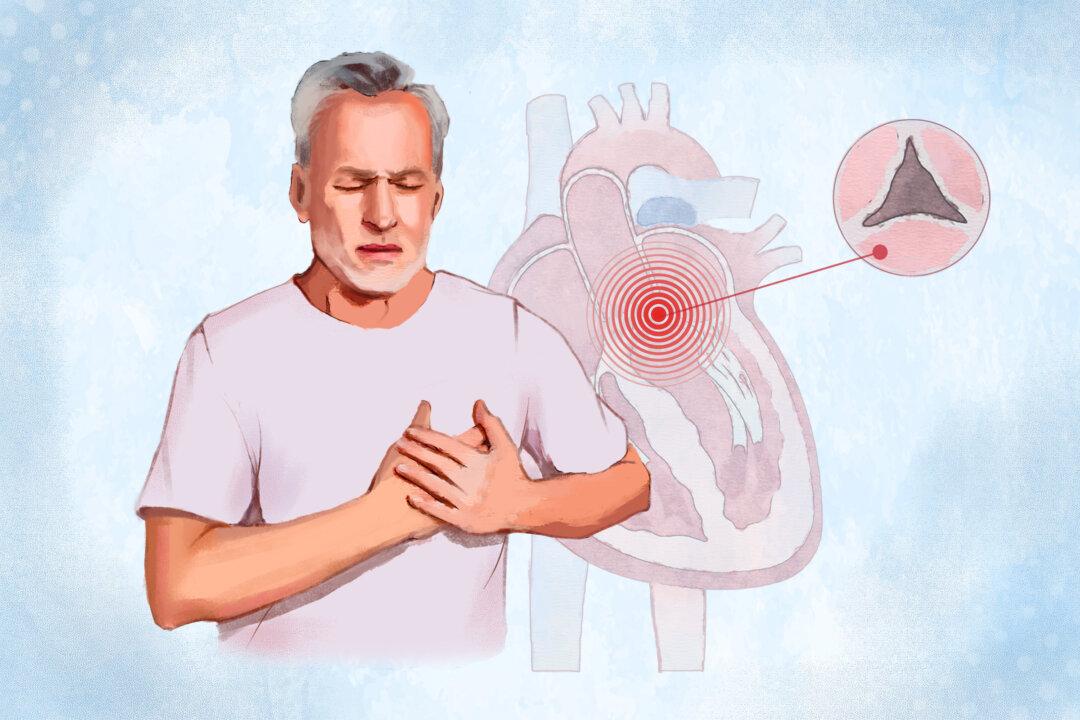

Better glucose control means less risk of complications caused by diabetes, including cardiovascular disease and peripheral nerve damage.Glucose is fuel for the body, particularly the brain, and an adequate amount of glucose must constantly circulate in your bloodstream. When blood sugar is too low, the brain doesn’t have enough fuel and can become comatose; when it’s too high, it can damage our blood vessels.

A healthy body has many physiological processes to keep blood sugar within that tight range, and one of the most important is insulin.

The low insulin sensitivity is initially brought on by eating excessive amounts of sugary and processed foods and reduced physical activity. The pancreas secretes insulin to compensate for high blood glucose levels, but as cells become less sensitive, more glucose circulates in the blood, and prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes becomes imminent.

“In short, any movement is good, and more is generally better,” Mr. Malin said. “The combination of aerobic exercise and weightlifting is likely better than either alone. Exercise in the afternoon might work better than in the morning for glucose control, and exercise after a meal may help slightly more than before a meal.”

Overall, the type and timing of exercise are vital to glucose control. Still, the most important thing is to stay active, even if it’s breaking up long periods of sitting with walking around for five minutes. The more you move, the better glucose control you will have.