How different would things be—how much healthier and happier would we be, as individuals and as a society—if we took the approach that innovations to our way of life were likely to be harmful until proven otherwise?

What past harms might we have prevented by waiting for tests or studies, by having been less eager to take things at face value, and by thoroughly having assessed new and needed innovations for unforeseen consequences?

Very soon, for the first time in history, Americans will be able to eat chicken meat that hasn’t required the slaughter of a chicken to produce. All the nutrition, all the taste, without the cruelty of factory farming or the resulting dreaded carbon emissions. If you think this sounds too good to be true—you’d be right.

Although producers of lab-grown meat such as GOOD Meat claim that their product is indistinguishable from meat as we know it—cultured meat isn’t a copy or approximation of meat: it is meat—the truth is that this new product differs in one fundamental respect from the meat you or I are accustomed to eating.

Most forms of lab-grown meat are made with, what are known to scientists, as “immortalized cell lines,” cells that, whether naturally or through intervention (such as exposure to radiation, genetic modification, or the use of an enzyme), replicate without end.

Makers of lab-grown meat like immortalized cell lines for much the same reasons scientists do. Once you’ve got the cell lines, you need never take another sample from an animal again. This means, among other things, that you can market the product as “cruelty-free” and suitable even for vegetarians and vegans.

This isn’t just an image problem for lab-grown meat, which, as part of the “alternative foods segment” already has to deal with deeply unfavorable attitudes among the general public. Numerous studies and opinion polls have already revealed that, given a free choice, the majority of consumers do not want to eat products like “plant-based meat” or “plant-based milk.” Rightly, they don’t believe the health or taste claims made in favor of such products.

Some smaller producers of lab-grown meat are now trying to use technologies other than immortalized cell lines because they know “cancer” can only be a disastrous association for a food product to have. It’s unclear whether they’ll be successful. Nevertheless, the so-called Big Three—GOOD Meat, Upside, and Believer—continue to plow on with their use of this technology.

But while the scientists Bloomberg interviewed for their piece on lab-grown meat said they don’t believe eating immortalized animal cell lines could actually give you cancer, the truth is we can’t be so sure. As I say, there is no history of consumption of such products in our dietary history stretching back hundreds of thousands of years. There are no long-term safety data for anybody—be they the CEO of Eat Just, a representative of the FDA, or a Twitter commentator—to point to.

Cancers create bubbles, otherwise known as exosomes, by means of which they can transfer genetic material into healthy cells and turn them cancerous. There’s absolutely no reason to doubt, then, that cancer-causing genes in lab-grown meat (otherwise known as “oncogenes”) could be taken up into the genome of an eater, potentially anywhere in the body, with disastrous effects.

So why are we speeding towards a situation where people could be eating lab-grown meat as regularly as they eat real meat now?

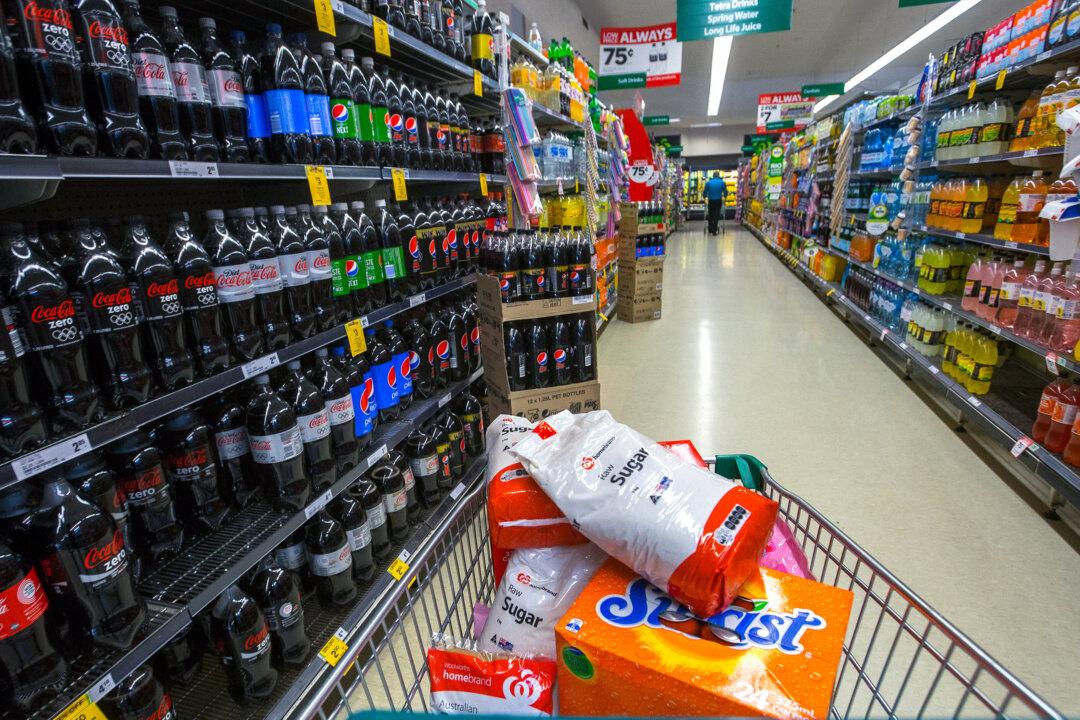

Whether we’re talking about aspartame, high-fructose corn syrup, or genetically modified crops, the decision to proceed at pace with their massive incorporation into our diets has been the corporations’ gain and our loss.

The transition to a global plant-based diet, ostensibly in the name of saving the planet from climate change and feeding a world population that will reach 10 billion by mid-century, will allow corporations near-total control over the food supply. This is the foundation of the Great Reset.

It’s not just our food that is subject to the cavalier attitude of “safe until proven otherwise.” This isn’t a glitch in the system. Our environment is now bathed in harmful chemicals, especially, but not exclusively, chemicals related to plastics because we allowed ourselves to become totally addicted to them, long before we knew the mistake we’d made.

One unfortunate side effect of the current licensing rules for chemicals is that, even when a chemical is identified as dangerous, the replacement often turns out to be as bad as, if not worse than, the chemical it replaced.

I’m not making an argument that we should resist all innovation. Innovation, when it brings desirable change, is to be welcomed. I’m writing this article on a personal computer, a marvel of technology that has made my life immeasurably better—although it does sometimes provoke frustrations when compared to a simple typewriter or paper and pen.

What I’m saying is that we should make room, as a society, to be able to think a little longer and a little deeper about the potential consequences of new products and technologies—especially when their aim—like lab-grown meat and other alternative proteins—is to disrupt habits that have served humans perfectly well from the dawn of time.

Making such room wouldn’t be easy, though, as it would mean challenging some of the most powerful vested interests in the world today. For them, time is money. For the rest of us—it’s the difference between sickness and health.