“Fasting” was Musk’s not-so-surprising first response (fasting is very trendy now, especially in the tech world). The follow-up—“And Wegovy”—was rather more surprising, if only for its honesty.

Musk’s admission to his 116 million Twitter followers—and the world—that he had used Wegovy—also known as Ozempic—was a huge boost to the profile of the not-so-secret weight-loss “wonder drug” that many other celebrities are using, although most won’t dare admit it. In a way, it was only fitting that Musk, the man who bought Twitter at a huge cost because he believes in open and free speech, should help blow the lid on just how widely used this new drug is among the glitterati.

If your favorite actor or actress has recently lost a noticeable amount of weight, chances are that they’ve been using Wegovy. One of the tell-tale signs is the so-called Ozempic face, a gaunt look caused by the loss of facial fat. Although buccal-fat removal is now an increasingly common procedure in which fat from around the cheeks is surgically removed to give the face a harder, more angular look, it’s just as likely that celebrities are using Wegovy.

Semaglutide, the drug’s proper name, was created by Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk as a treatment for Type 2 diabetes in 2012. Clinical trials began in January 2016 and were completed in May 2017. The drug is injected and works by mimicking a natural gut hormone called GLP-1, which is responsible for regulating insulin and blood sugar levels. In basic terms, the drug helps to curb hunger pangs and makes the user feel full for longer. If you don’t feel hungry, you won’t eat, and if you don’t eat, you’ll start losing weight: It’s that simple.

Many drugs start as treatments for a condition different from the one they ultimately become known for treating. Viagra was a blood-pressure medication before users reported that it had a surprising and, in many cases, not unwelcome side effect.

Semaglutide was first approved for use as a diabetes treatment under the Ozempic brand, not long after clinical trials came to an end, and then later approved as Wegovy, a higher-dose treatment for obesity in the United States, the UK, and the European Union.

The buzz about semaglutide and its fat-busting effects had been building for some time before Musk’s tweet. By 2020, it was already the 129th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 4 million prescriptions. After a shortage of Wegovy in the United States, doctors began prescribing Ozempic off-label as a fat-loss treatment.

Shortages of Ozempic have also been reported in Australia, where new prescription guidelines had to be issued to prioritize the diabetes patients for whom the drug was originally developed. These failures to meet the growing demand for semaglutide led Novo Nordisk’s competitor Eli Lilly to state that it was working “around the clock” to make sure there was an adequate supply of its drug tirzepatide, which functions similarly.

In the first nine months of 2022, Novo Nordisk reported a 59 percent growth in sales of Ozempic and Wegovy. Social media, especially TikTok, are now awash with videos about semaglutide and its miraculous effects. The tag “#ozempic” has hundreds of millions of views on TikTok alone. Given all of this attention and positive coverage, it’s perhaps no wonder that semaglutide is already being hailed as the “solution” to obesity.

The study also found that women gained nearly twice as much as men over the same period and that younger adults gained the most overall, at an average of 17.6 pounds between their 20s and 30s. Over a lifetime, the combined weight gain adds up to 45 pounds, more than enough to push most people into the category of seriously overweight or even obese.

A problem on this scale obviously requires a bold approach. But what’s bold about creating a drug that does nothing to address the real causes of the increasingly overweight, unhappy world we live in?

Champions of semaglutide claim that it’s, above all else, a compassionate treatment for weight problems, since traditional approaches—eating less, moving more—don’t really work. Some of us just weren’t made to be a normal size; it’s in our genes to put on weight, and so as soon as we’re put in a modern environment of abundance, we end up overweight. It’s something like a law of nature: It’s irresistible.

How could it be otherwise? Semaglutide works by stopping you from eating, and your caloric needs then outweigh your intake, causing you to lose weight. The drug doesn’t alter your genetics.

The fundamental truth is that in the past hundred or so years, we in the developed world have undergone a profound transformation in the way we eat and live. We’ve effectively broken with the past and the lifestyles of our ancestors, who lived active lives—often of toil, for sure, but not always—and consumed diets overwhelmingly composed of natural, whole foods.

In the best instances, people in traditional societies, such as those described by the famous dentist Weston Price in his 1939 book “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration,” were able to flourish on rich diets of nutrient-dense animal foods—organ meat, fatty cuts, seafood, dairy, eggs, and fat products such as butter and lard—and displayed a health and vitality that eludes all but the most fortunate of us today.

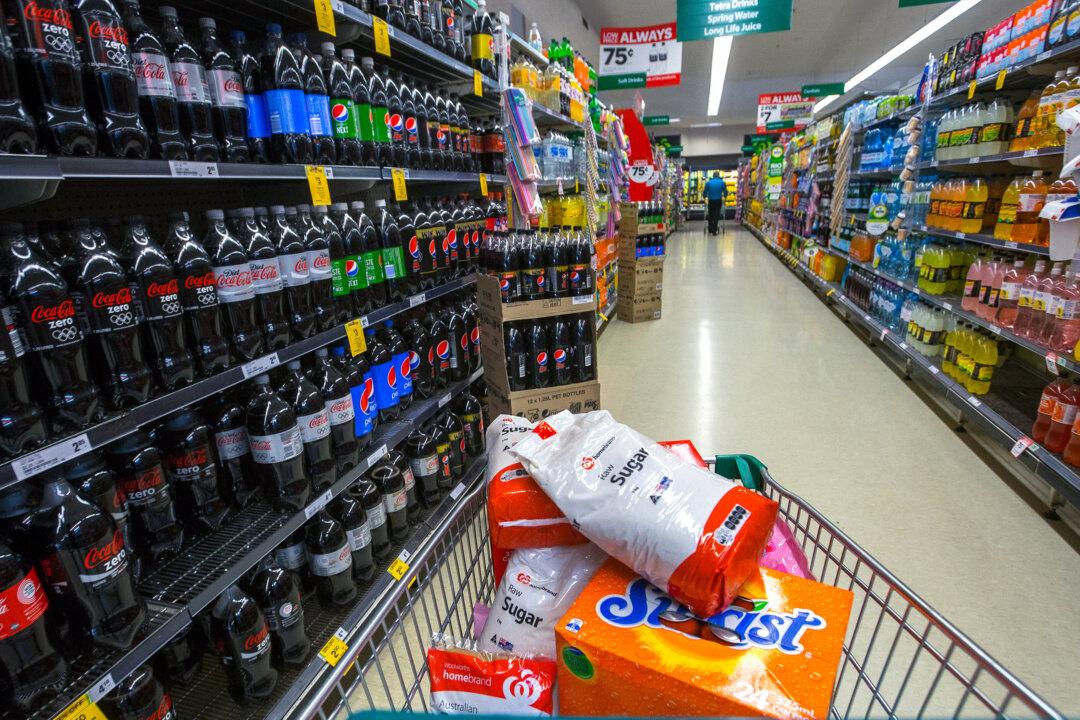

Now what do we eat? Processed foods loaded with added sugars, refined grains, toxic seed, and vegetable oils—once thought fit to be used only as industrial lubricant—and a witch’s brew of colorings, flavorings, texturizers, and other additives. These foods have come to make up an increasingly large part of our diets over the past century, and the results have been disastrous.

Study after study has linked this kind of food with every possible ailment you could care to imagine, from autism to Alzheimer’s—including, of course, obesity. A 2021 BBC documentary titled “What Are We Feeding Our Kids?” revealed that consuming processed food in typical quantities for just a month can actually rewire the brain’s pleasure and automatic-behavior centers in the manner we might expect of a drug addict, in addition to causing weight gain, anxiety, loss of libido, hemorrhoids, and a wide variety of other nasty problems. These worrying brain alterations persist even if you stop eating processed food.

The addictiveness of processed food isn’t a side effect; it’s by design. Armies of highly paid food scientists labor to ensure that processed food products are “hyper-palatable,” hitting the “bliss point” where qualities such as crunchiness, sweetness, and saltiness are perfectly balanced. The food is easy and, most of all, satisfying to eat.

Manufacturers of processed food love it not just because it’s highly addictive and people can’t stop eating it but also because it has a great shelf life and is extremely cheap and easy to make. All processed food is made from the same basic ingredients: things such as corn meal, soy meal, refined wheat, partially hydrogenated vegetable or seed oil, meat, and protein meal. All that really differs from one type to the next are the ratios of ingredients. With just a few ingredients, you can create virtually any processed food you want, from dog kibble to Twinkies and everything in between.

A handmaiden to this fundamental change in our diets has been the creeping medicalization of our societies. The perils of surrendering more and more control to the medical profession have been thrown into stark relief by events of the past three years. But medicalization and its negative effects, otherwise known as “iatrogenesis,” are virtually everywhere we care to look in our lives today.

We see iatrogenesis, too, in the massive overprescription of antidepressants, pain pills, and blood pressure medication to cope with the debilitating effects of a diet and lifestyle that are radically at odds with those of our ancestors.

By surrendering to the logic of ad hoc treatment, we concede that the underlying problems, whatever they may be, can’t be solved. This is exactly what Ozempic/Wegovy is: yet another concession that we lack the will to confront our problems today as they really are.

Of course, massive entrenched interests in the food and medical industries, which hold powerful sway over government, confront anybody who would dare to suggest a wholesale change to the way we live and eat. A month’s supply of semaglutide can cost about $1,000 in the United States, and many users will likely have to remain on the drug indefinitely to keep the weight off if they aren’t prepared to make any other changes to their lifestyle.

Just imagine: tens of millions of overweight people hooked on this expensive drug for decades. What a proposition for the shareholders!

The shareholders will profit, but it will be at our expense. By ignoring the root causes of obesity, we'll be no closer to real health than we were before, however much less some of us may weigh.